DeLoggio Achievement Program

Selection of and Preparation for College and Professional Programs

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

Learning How to Think

One of the gravest problems in education in the United States and in most of the rest of the world is that knowledge is memory-based. In order to be a professional, whether a lawyer, a doctor, or a business consultant, you have to know how to diagnose and solve problems. Of course, this requires having a database of knowledge in your head and at your fingertips, but it also requires having analytical skills that are rarely taught at any level except in the most elite schools.

In the United States, this failure is more common in public schools, where end of grade tests measure one's ability to report memorized material rather than to develop ideas and creative proposals. The posts in this section will explain why such skills are necessary, and how to acquire them. They will also link to sources of ideas, historical knowledge, and current events.

Teaching how to Learn

Why Are Finland's Schools Successful? “We prepare children to learn how to learn, not how to take a test,”

said Pasi Sahlberg, a former math and physics teacher who is now in Finland’s Ministry of Education and Culture.

I watched an accompanying movie, but didn't feel like it helped much, so I'm not linking it.

In the meantime, however, I did learn something about how I learn. I wander through the world picking up various pieces of unrelated trivia and storing them away for no known reason except that I might need them sometime. I'm sure there are people who have more "knowledge," by which I mean a body of interrelated concepts, than I do; but I'm not sure that there are nearly as many people who know that the movie "Moonstruck" starring Cher and Nicholas Cage, is a remake of Walt Disney's "Lady and the Tramp." You see what I mean by unrelated trivia.

|

|

Eventually the pieces of unrelated trivia build themselves a bridge, and I come to a new understanding. And this explains why I teach people by spending an enormous amount of time filling their brains with YouTube clips, Wikipedia articles, snippets of music and Google images. Because you never know when the right pieces are going to connect themselves into a new concept.

Reading Makes You Think

Thinking While You Read Makes You Smart

This info came to me in an email from "Lumosity," a web site and business to increase your intelligence, particularly problem-solving skills. I couldn't find the article itself, so I'm pasting the quote here:

What is the value of an English literature class — could you read on your own time and experience the same benefits? In a recent interdisciplinary collaboration between Stanford neurobiologists and assistant English professor Natalie Phillips, researchers used the Jane Austen classic Mansfield Park to investigate how the type of critical reading taught in most English classes may alter brain activation patterns.

... Phillips and researchers from the Stanford Center for Cognitive and Neurobiological Imaging used an fMRI machine to scan the brains of 18 participants as they read a chapter from Austen’s Mansfield Park. First, the participants were asked to read the chapter casually, as they would for fun. Then they were asked to switch to close reading, a common term for the type of scrutiny to detail and form required to analyze text in a literary course. To ensure that participants could successfully switch between these two modes of reading, all participants were PhD candidates pursuing literary degrees.

Researchers observed a significant shift in brain activity patterns as the PhD students went from casual to critical modes. Critical reading increased bloodflow across the brain in general, and specifically to the prefrontal cortex.

... Though it’s still too early to understand exactly what the future of this new branch of research holds, Phillips suggests that critical reading could one day be seen as a valuable tool in “teaching us to modulate our concentration.”Words Have Meanings

I don't know why we demand precision with numbers and allow incredible sloppiness with words. If someone said, "six and eight are about a dozen," we would either kindly correct them or cruelly laugh at them. But we gladly let someone say, "we learned some stuff about the Civil War this year."

What stuff? Battles, generals, and dates? Philosophy and sociology? Political machinations? "Stuff" is one of the words that we use to save ourselves the trouble of learning how to think about language.[Moved from DeLoggio facebook of March 14, 2015] My favorite twisters of language, the MinuteMen, gave me a delightful example of incorrect use of language. Here's the exact quote:

"Just a few days ago, some brave Minuteman Project supporters and I illegally crossed the border and stood on Mexican territory."

Minutemen storm Mexican Consulate, demand the same “freebies” from Mexico that are provided to illegal aliens in the U.S.In fact, they entered the Mexican Consulate in San Bernadino.

A Consulate is legally the territory of the country it represents. But they didn't enter it illegally. You and I can drop in the next time we're in California. They did some rude things and were asked to leave, which they did. So what was "illegal"?Did they "cross a border"? San Bernadino is 120 miles north of Tijuana and 80 miles east of Los Angeles Airport (LAX). My understanding is that it's legal for U.S. citizens to enter Mexico. And if you do anything illegal after you get there, you still didn't get there illegally.

William Zinser's "Writing to Learn" teaches that the best way to learn to think precisely is to teach a subject. By the time you've answered every student's question about the word "stuff," you will know exactly what you have learned about the Civil War.

As a parent, you can teach your child how to use words precisely by learning a subject with the child. Watch a YouTube clip, or read a book together. Discuss each thing that you've learned, and what each word means. As you learn to teach your child, you'll be amazed to see how much your vocabulary improves at the same time that your child learns that words have meanings, and that precision of vocabulary brings with it precision of thought.It's Not That Simple

Perhaps it's a function of youth and the lack of comparisons that necessarily accompany a lack of years, and perhaps it's the fault of adults for teaching children in sentences that include "must" and "thou shalt not." But Youth likes absolutes, and doesn't do well with "it's not that simple."

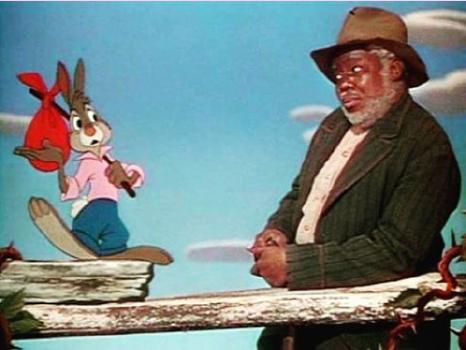

Some time ago I downloaded a brief biography of James Baskett, more famously known as Uncle Remus. The grand opening of the movie "Song Of the South" was at the Fox Theater in Atlanta; James Baskett was not allowed to attend the opening of "Song Of the South" and Walt Disney declined to attend the opening for that reason. Mr. Baskett was not nominated in the category of best actor, and both Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper and Walt Disney himself lobbied the Academy vigorously to present him with a special Oscar. He received it three months before he died.

Walt Disney is frequently accused of racism, and by today's standards, I would agree. When Disneyland first opened, he wanted every employee to be white and blonde, because he wanted Disneyland to represent small town America, and to him, the archetype of the small town American was white and blonde.

So how does a man who insists on white employees and believes that product requires a certain appearance boycott the opening of his own movie because the black actors are not allowed to attend, and fights for their right to win Academy Awards, even though Blacks were not nominated, because everyone knew that James Baskett had turned in a brilliant performance, reconcile these differences in his own principles and integrity?

I don't have an answer; I doubt that anyone does. That's my point; I'd like us to be thinking about this.

And that's a whole separate issue from whether “Song of the South,” as written by Joel Chandler Harris, or as adapted to by the Disney Studios, was racist. And none of those discussions even get close to the analysis that Barbara Hambly uses in her historical series that begins with the book, "A Free Man of Color," in which the protagonist Benjamin January (or in French, Janvier), claims that the Uncle Remus stories are allegories to help slaves escape the white boss; Brer Rabbit represents the field hand, and Brer Fox and Brer Bear are the slaves’ supervisors and owners.

A story that black slaves may have told each other to help each other escape to freedom was turned into a book of children's tales 50 years later. 65 years after that, Walt Disney turned it into a movie, whose ultimate message is about the potential dangers of segregation; yet 20 years afterwards, it was seen as a celebration of slavery instead of a statement against it. And the individual actions of Walt Disney, and the work to get an Oscar for a black man who was already dying of heart problems that were probably complications from diabetes, a humane and caring act, is lost in the symbolism that each group wants to attach to the part of the story that symbolizes something personal, whether or not that was anyone's intention.

And you know what? It's not that simple.

The DeLoggio Philosophy of Education

Copyright Take me to Home Page